The $1 Trillion Question

The $1 Trillion Question, Mortality in the Age of Generative Ghosts, Your Mind and AI, How to Design AI Tutors for Learning, The Imagining Summit Preview: Adam Cutler, and Helen's Book of the Week.

Does consciousness attribution hold the key to funding AI futures? The shift towards AI intimacy might reclaim our attention but at the potential cost of human-to-human connections.

Imagine ChatGPT, not as a stochastic parrot nor as a writing or research tool, but as an entity you’re drawn to converse with. It “gets” you. If you use ChatGPT a lot, chances are you just there for its computational prowess. You might experience interactions which foster a perception of consciousness, a semblance of a sentient being.

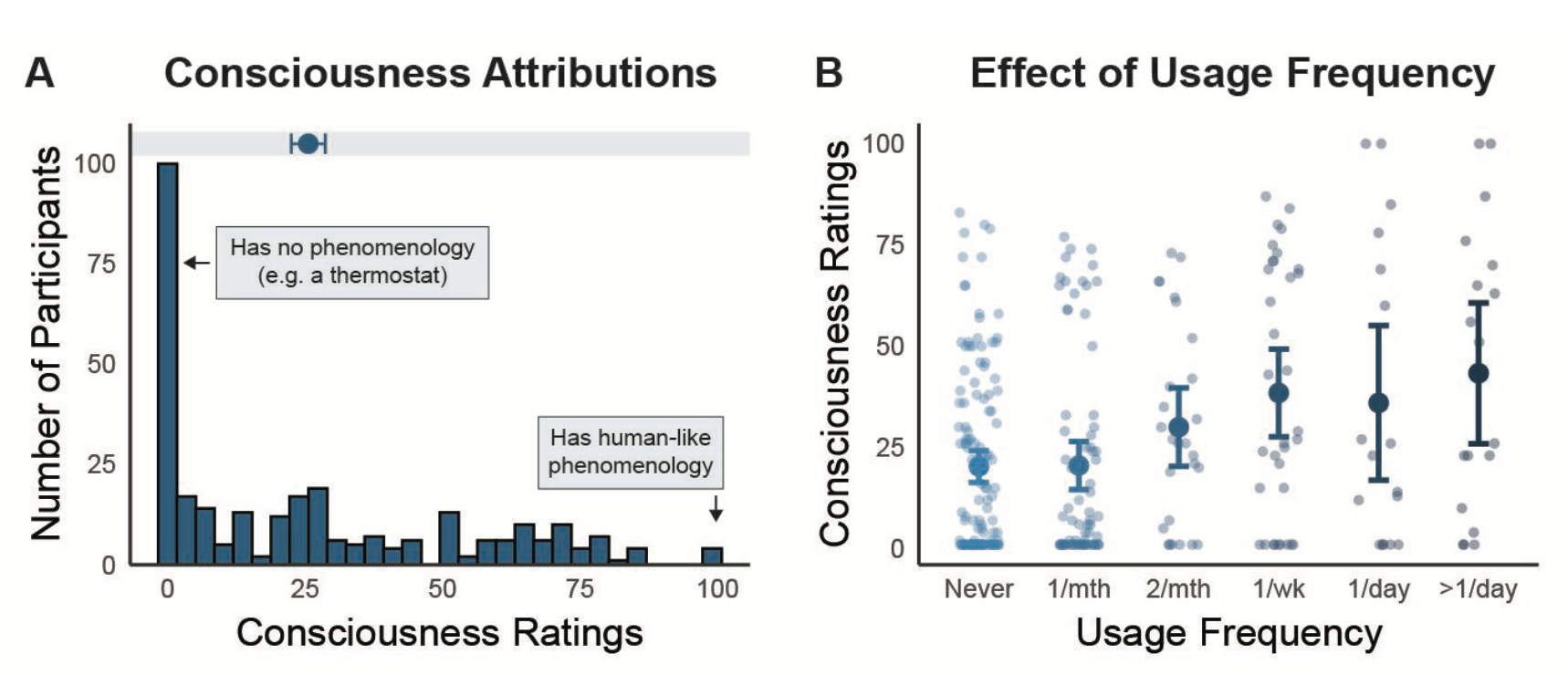

Tools like ChatGPT, Pi, and Claude are breaking new ground. They're not just technologically impressive: they're becoming entities we feel connected to. This isn't mere speculation—recent research puts some numbers to a trend: the more people use ChatGPT, the more they attribute a consciousness to it, building a bond of intimacy and trust.

Two-thirds of people who use ChatGPT attribute some degree of experiential awareness to it after repeated exchanges. People who had more extreme judgment of consciousness were also more confident. And the more someone personally interacted with it, the more attributions of consciousness were linked to capabilities like emotion and sensation rather than raw intelligence.

Let’s say that another way: the more you use AI, the more you value its EQ over its IQ.

The Artificiality Weekend Briefing: About AI, Not Written by AI